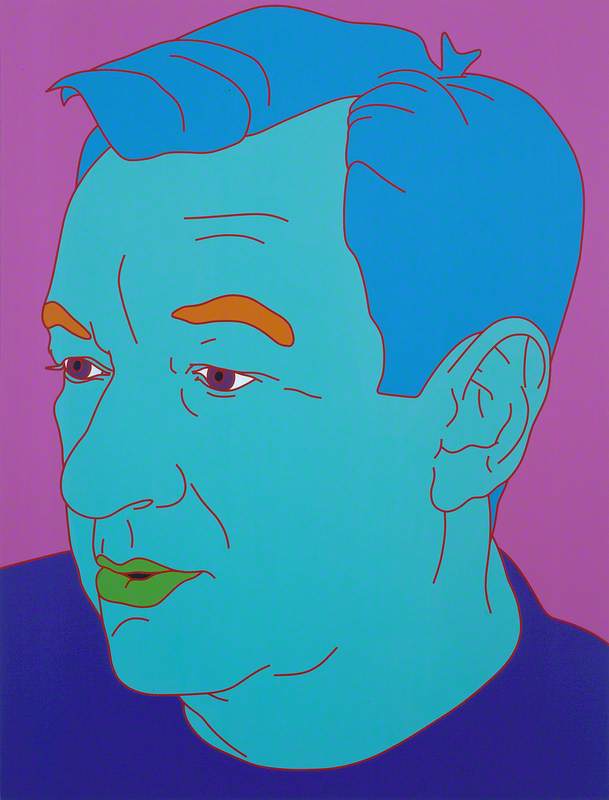

Michael Craig-Martin. Irish artist, writer, and teacher. He was born in Dublin, moved to the USA as a child, and studied at Yale University, where he encountered an important early influence, John Cage's ‘Lecture on Nothing’ (1949). ‘Life without structure is unseen. Structure without life is dead.’ Although Josef *Albers was no longer there in person, his teaching system remained and Craig-Martin was impressed by the ‘intellectual coherence’ of his view of art (Tusa). In 1966 he settled in England, where he became one of the leading figures in *Conceptual art. His work was less concerned with verbal language than that of some of his contemporaries, more with developing the minimal box forms of *Judd and *Morris by introducing elements of paradox and spectator participation, as with the Box that Never Closes (1967, Swindon Museum and Art Gallery).

Read more

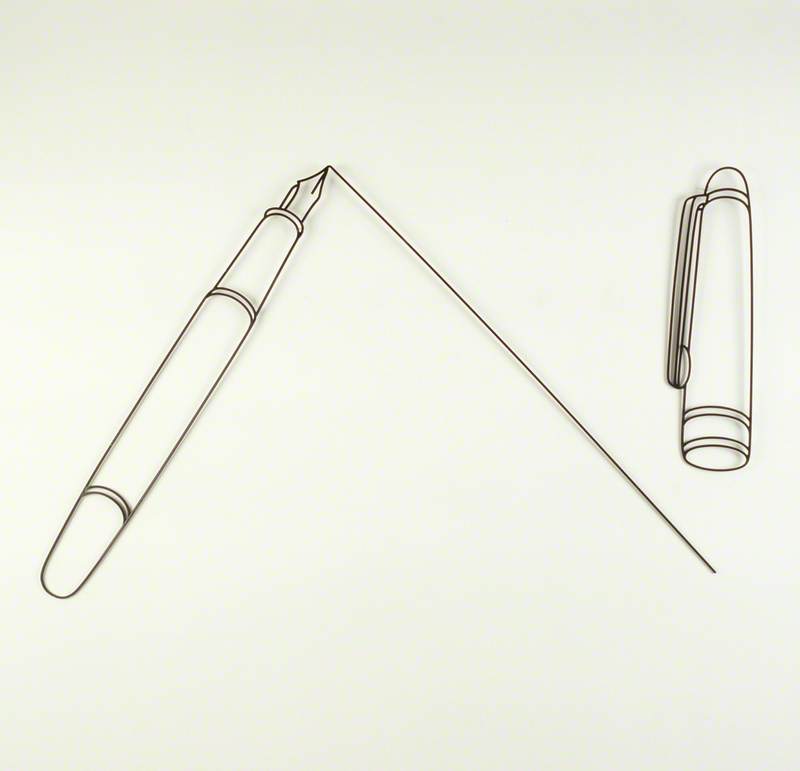

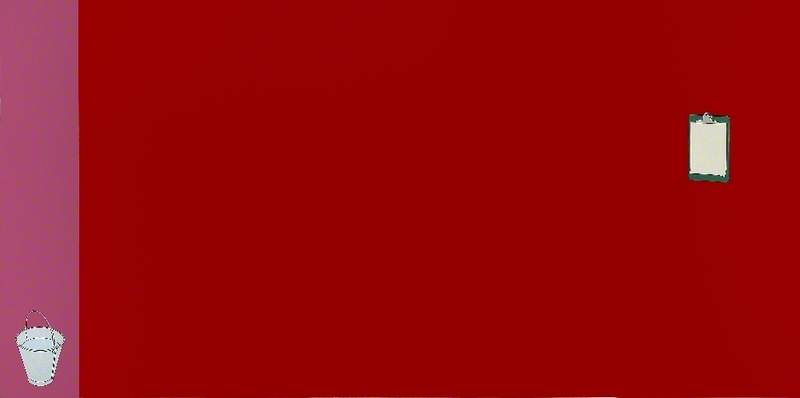

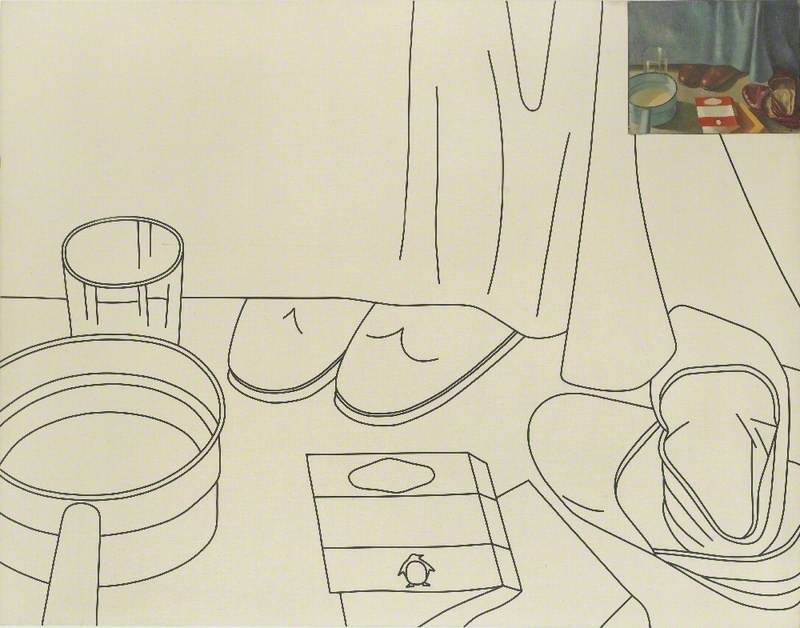

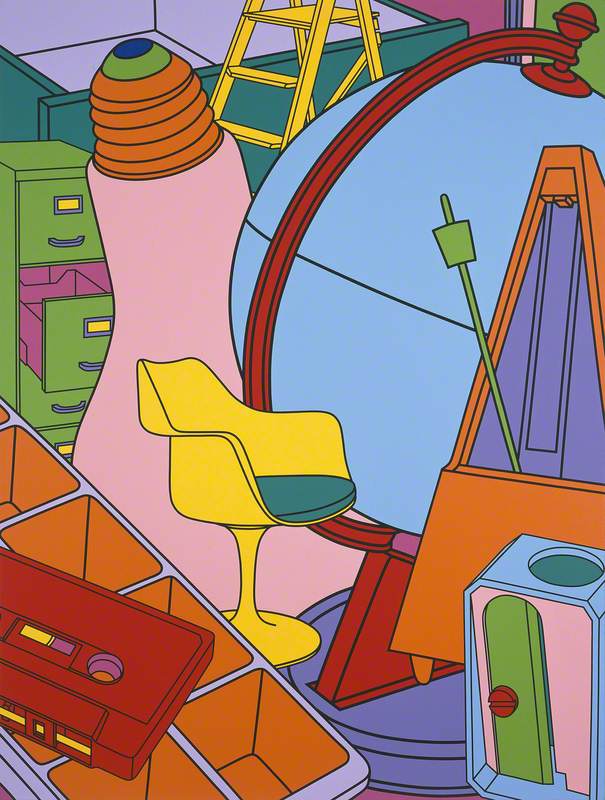

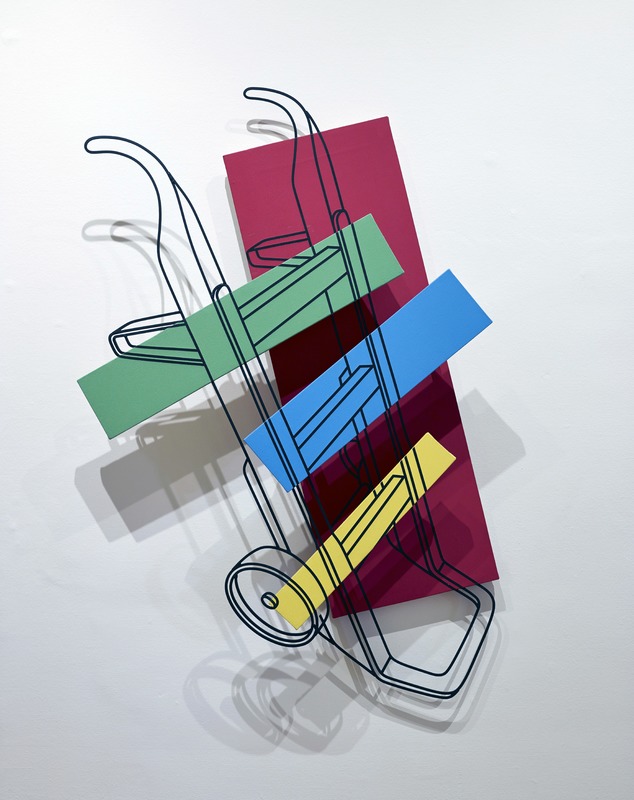

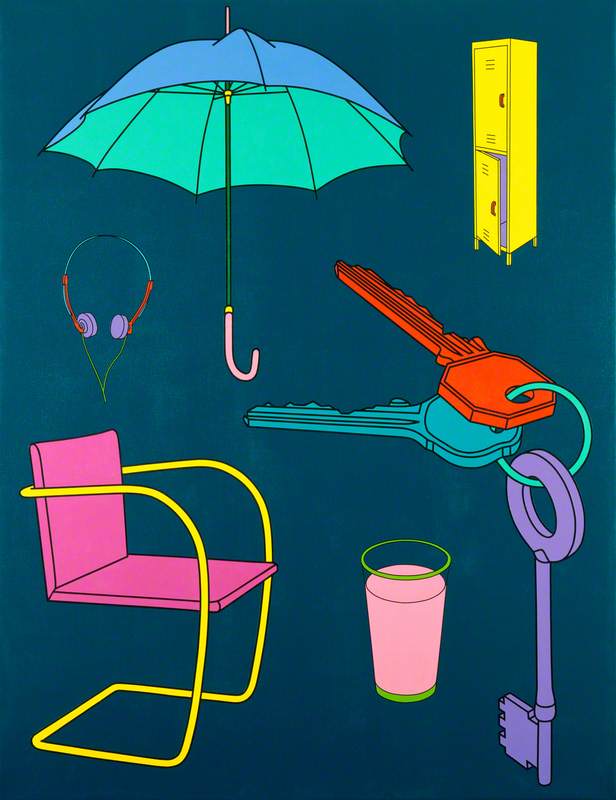

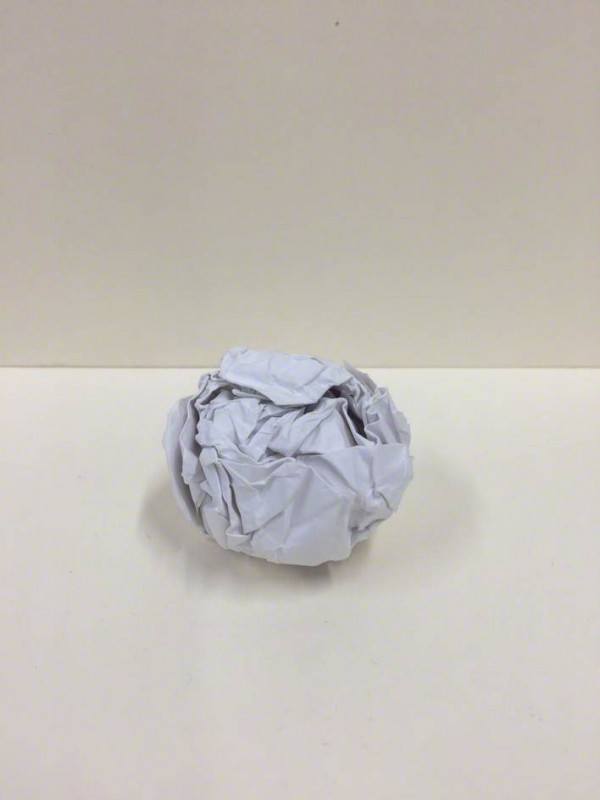

The best-known of his early works is An Oak Tree (1973, National Gallery, Canberra). When first seen at the Rowan Gallery in London, this glass of water on a shelf was the only object in the room. It is accompanied by a witty text in the form of an interview in which Craig-Martin takes the roles of both artist and viewer. As he put it later, ‘there's the part of me that believes it and there's a part of me that's sceptical and all of these things are played out in the one’ (Tusa). The artist insists that the oak tree is actually present in the glass, which is not just a symbol. ‘Q. Was it difficult to make the change? A. No effort at all. But it took me years before I realized I could do it.’ Some commentators have noted Craig-Martin's Catholic background and related the work to the doctrine of transubstantiation, whereby bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Christ without any change in the physical ‘accidents’. In the Cage lecture which had so impressed Craig-Martin, Cage referred to the lecture itself as being ‘like an empty glass into which anything might be poured’. In the late 1970s Craig-Martin embarked on a series of wall-drawings in which everyday contemporary objects, familiar from home or office, were depicted on a large scale as outlines in masking tape. In a statement on these works he explored the role of ‘picturing’ and its distinction from the ‘forming’ which had been the basis for much 20th-century art. (‘Picturing’, Artscribe, no. 14, October 1978). The context of this work and theory was a tendency, especially in the English-speaking art world of the period, to be largely dismissive of abstraction in the demand for socially relevant content. At the same time he argued that this concern for ‘content’ was leading to an unquestioning acceptance of models borrowed from ‘the authority of the past’. Craig-Martin was putting into the foreground the actual process of ‘picturing’, often taken for granted because of the ‘constantly generated’ supply of pictures from television. The objects are frequently shown from a three-quarters angle from above so as to emphasize their spatial dimension in contrast to the two-dimensionality of the black line. The objects are also superimposed and contradictory in scale. This concern with the process of picturing and perception can be related to his admiration for the art of the Italian Renaissance: ‘I like the sense that you are watching them making discoveries. It's an amazing moment in human history’ (interview with Rachael Thomas, 2006). The outlined pictures of objects later acquired brilliant colours. A typical example is Eye of the Storm (2003, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin), in which an open safety pin hovers above a bucket and a long-handled garden fork is propped against a light bulb. Craig-Martin has also had a distinguished career as a teacher. At *Goldsmiths College in London he has been the mentor of several of the *Young British Artists who became prominent in the 1990s, including Damien *Hirst and Sarah *Lucas. Public works include Big Fan (2003, Regent's Place, London), a giant light box. Further Reading R. Thomas, Interviews with Michael Craig-Martin (2006) Michael Craig-Martin interviewed by John Tusa, BBC website.

Text source: A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art (Oxford University Press)