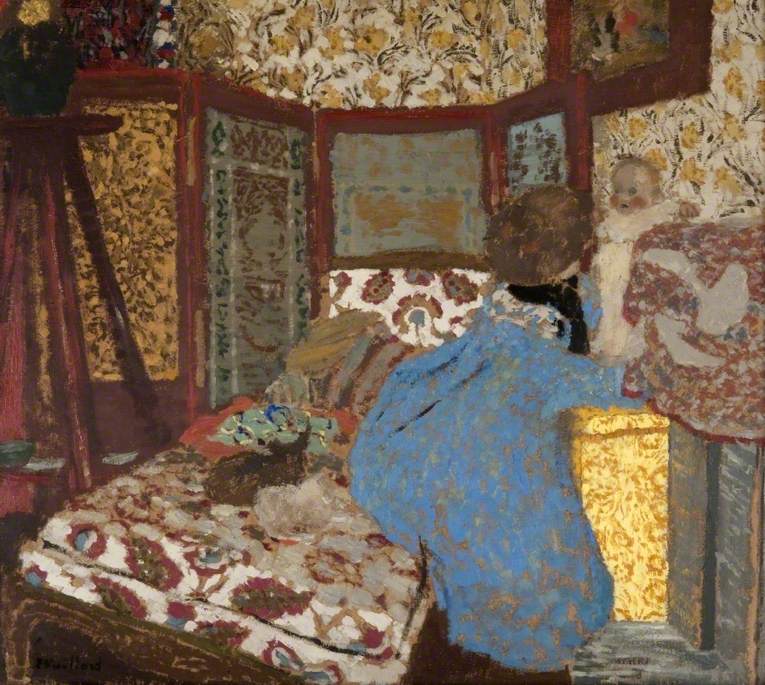

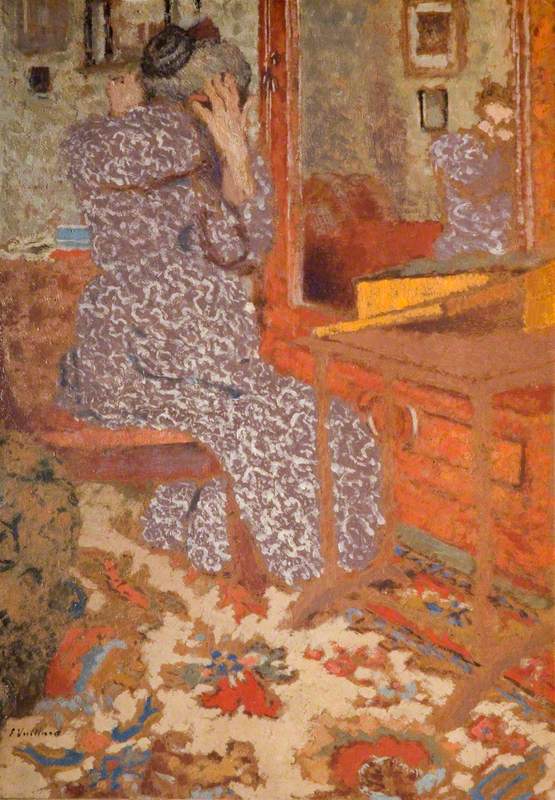

The title of the painting tells us what it is about, but if we look closely, it doesn't make sense.

Madame Vuillard Arranging Her Hair

1900

Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940)

The hands that are purportedly arranging her hair don't much look as if they are doing that, nor do they look like they are even connected to her own body. The hands (that don't seem to be reflected in the mirror – or is one of them a hand that obscures the reflection of her face?) might almost belong to some kind of disembodied magician, or as the French refer to them; a prestdigitateur (using digits to conjure), and the fact that there is one dominant hand also encourages us to view this as a symbolic hand.

Madame Vuillard Arranging Her Hair (detail of hands)

1900, oil on millboard by Jean-Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940)

The hand represents the manual, the artist is manual, making magic with their hands. Vuillard's mother we know was a seamstress, and as such was a cloth artist and great influence on the way that Vuillard saw the world: in a suffusion of pattern. It is Vuillard's deeply empathetic understanding of the nature of textiles that exemplifies (and somehow justifies) his approach to painting. His visual world is patterned; blocks of pattern make up the forms that jostle together to describe interiors that exist as a conglomeration of dodged, scumbled paint. When he goes outside, the same technique is applied to landscape and suburban surrounds, accumulations of daubs and repeated jabs stand in for a variety of emotions and atmospheres, describing shape, and are subsumed into his formulaic methodology.

Madame Vuillard Arranging Her Hair (detail of dress)

1900, oil on millboard by Jean-Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940)

What is interesting about this working method is the fact that the images coalesce so successfully and open up to us his special vision. Simultaneously autobiographical, the paintings record his 'osmotically' acquired library of patterns, they are a tender salute to his mother (especially in this instance) and they are a formal acknowledgement of his position as 'patternist' within the trajectory of the history of art. His world is descriptive and figurative, but like a magician, he is revealing his work in the process of disintegration: the forms hover between substance and abstraction while the squiggles of her dress are active in a manner that foreshadows Jackson Pollock's action-filled painted 'carpets'. Vuillard's 'real' carpet is both middle-class furnishing and recounts the story of playground forms; animals let loose into the flattened space of a putty-coloured backdrop.

Madame Vuillard Arranging Her Hair (detail of mirror)

1900, oil on millboard by Jean-Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940)

The two central shapes containing pattern dominate the composition and divert our attention from the intrigue that is the mirror story, they keep us on the side of 'reality'. When our eyes stray into the reflected world, we must go, like Alice, through the formality of the wooden frame; all angles and straight edges that delineate the boundaries of the second mysterious space. The reflected form of Madame is sinister if we read her face within the mirror as a mask, or is that her hand?

This painting brings to mind Walter Sickert's Ennui, and indeed Sickert and Vuillard have much in common when we consider the often oppressive and stuffy nostalgia that these artists describe.

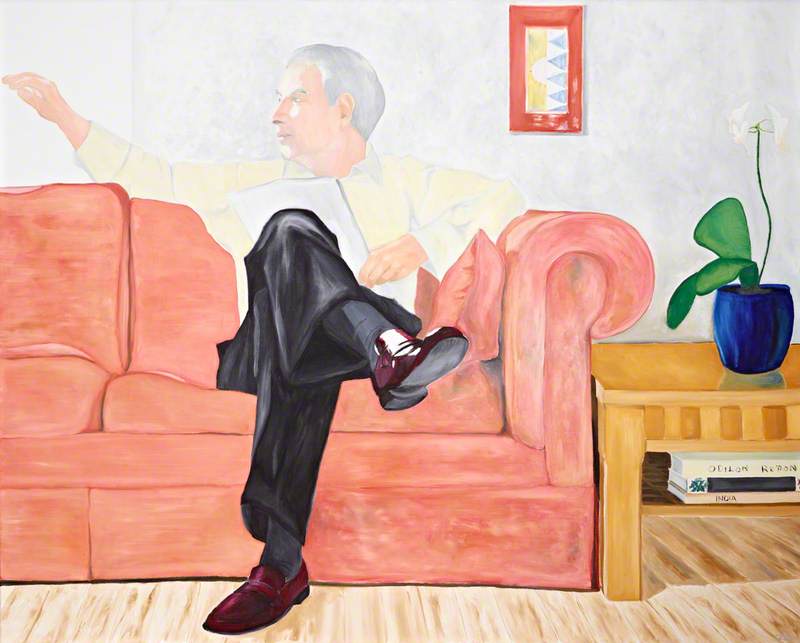

Liz Rideal, artist and writer