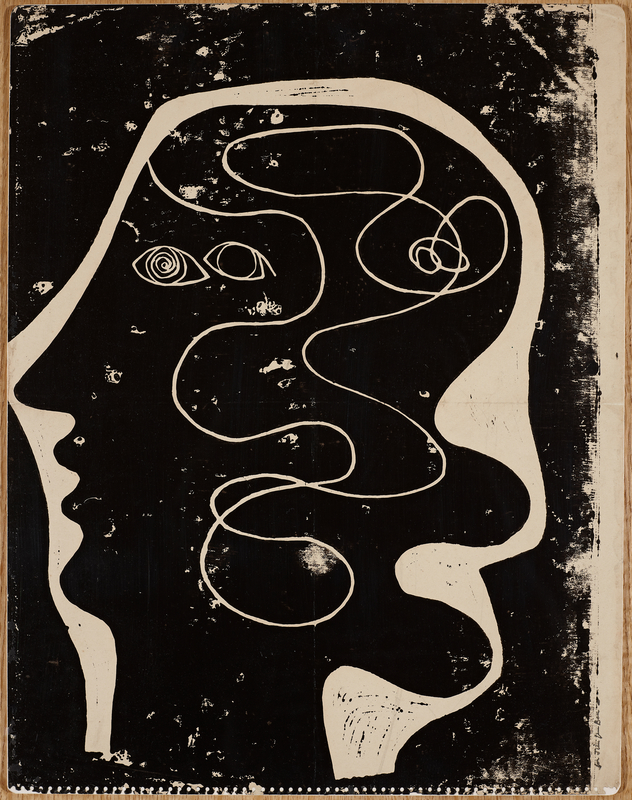

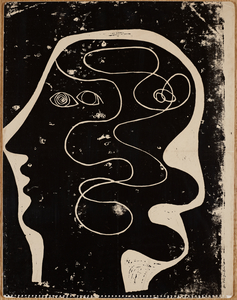

A woman's head appears in profile, like the bust of an ancient Greek goddess. Despite the side-on view, she has two eyes, one of which contains a spiral for a pupil. What looks like a piece of dropped string suggests messy curls. Though it is not made explicit in the title, it is clear from the head's distinctive silhouette that the profile is that of Barbara Hepworth.

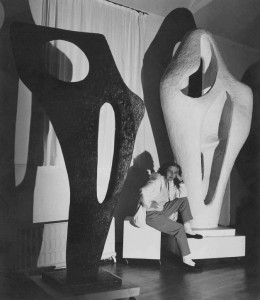

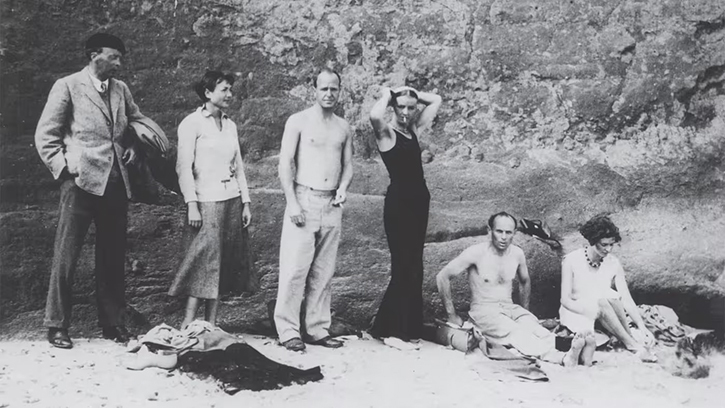

In the summer of 1931 Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth met on a seaside holiday in Happisburgh, Norfolk, where they were staying with a group of artist friends but without their respective spouses (Winifred Nicholson and John Skeaping). They quickly fell in love. In March 1932, Nicholson moved into Hepworth's studio in Hampstead, where this work was made.

Ivon Hitchens, Irina and Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Mary Jenkins on the beach

1931, photograph by Douglas Jenkins. Happisburgh, Norfolk

1932–34 (head) was created using the printmaking technique of linocut – a variant of woodcut in which an image is cut into the surface of a sheet of linoleum which is then inked with a roller and impressed onto paper or fabric. In this work, the image is printed straight onto a sheet torn from a notebook. The holes from the binder are still visible at the bottom of the page.

The simple inscription, 'for Jim, from Ben', suggests that the print was given directly by the artist to Jim Ede, the founder of Kettle's Yard. Nicholson and Ede were almost exact contemporaries, only a year apart in age. They met in the early 1920s, when Ede was a junior curator at Tate, living with his wife Helen on Elm Row in Hampstead, in a large house which became a lively meeting place for artists.

Ben Nicholson would regularly turn up to the Edes' house with his canvasses in tow. At the time he struggled to sell, or even give away, his works. Ede would buy them for little more than the cost of the frame. Ede was a firm supporter of Nicholson and there are over 60 works by him in the Kettle's Yard collection.

head hangs in the library at Kettle's Yard – in the same spot where Ede left it when he and Helen retired to Edinburgh in 1973. There are many other versions of the print. Three separate impressions appear in a picture of Nicholson's studio by photographer Paul Laib from 1934.

No. 7 The Mall studio

1933, photograph by Paul Laib (1869–1958)

The fact that three versions hung in Nicholson's studio suggests that the print's multiplicity was part of the artist's process of experimentation. The depth and evenness of the ink varies from one version to the next. So does the colour: some are a deep black, like the one at Kettle's Yard, while others are blue.

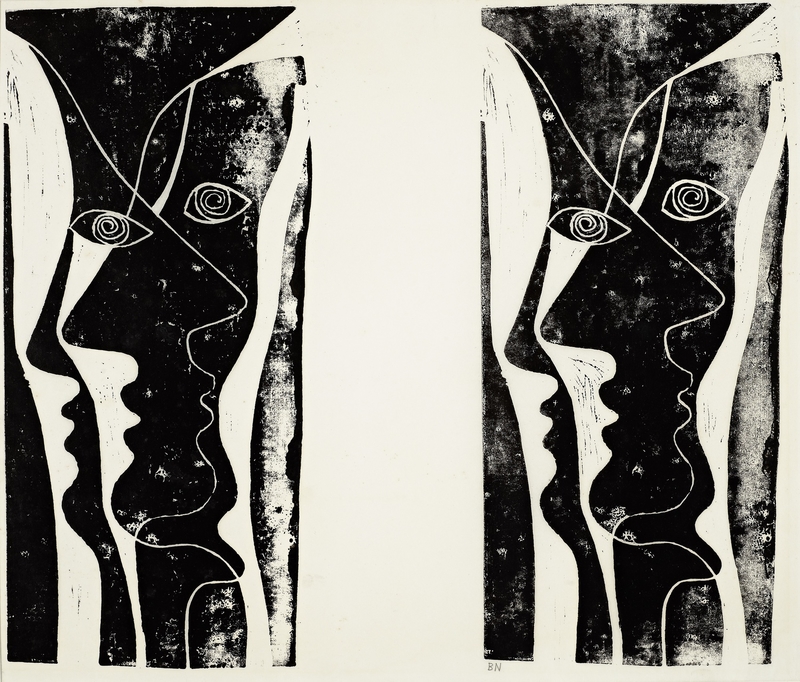

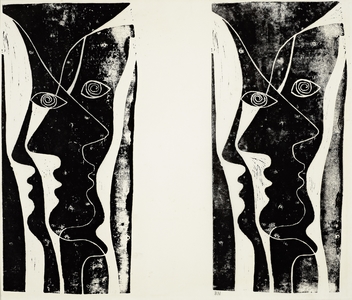

In at least one of the versions, the face has been printed twice, creating a double image.

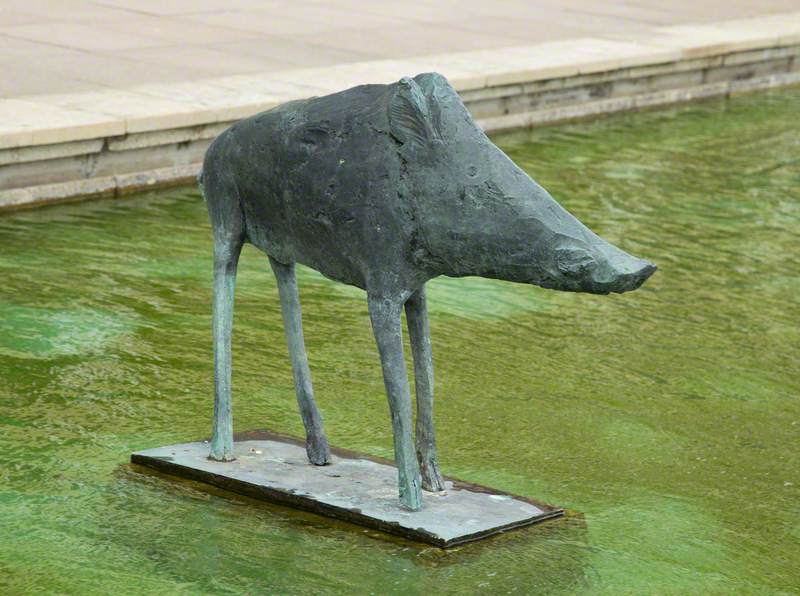

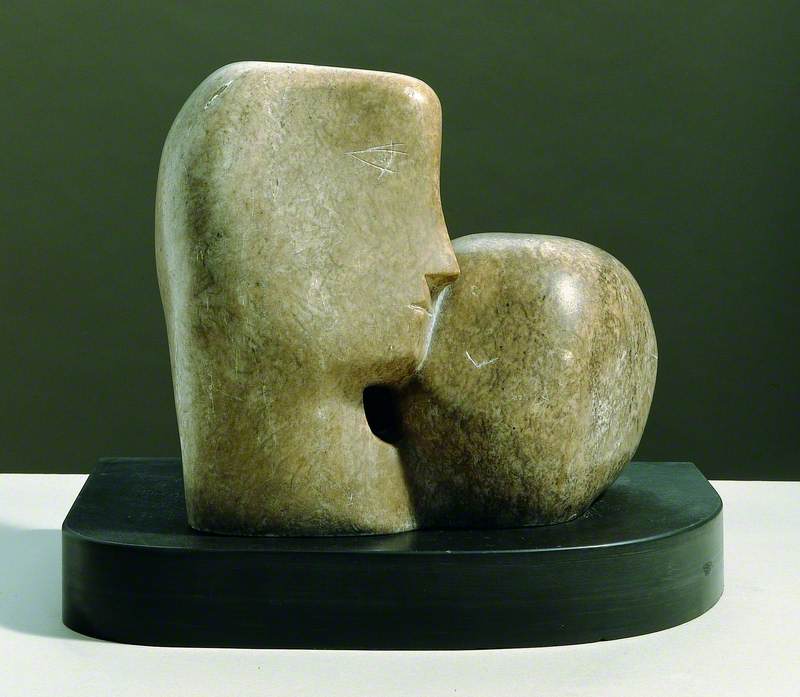

This relates the print to a similar work, also in the Kettle's Yard collection: 1933 (profiles). The same image appears in a series of linocut fabric pieces titled princess. Hepworth's likeness therefore became a motif in Nicholson's practice, repeated over and over again both across and within the works. Hepworth, too, began to depict profiles in her increasingly abstract sculptures – often in the form of two interlocking figures.

Hepworth had a transformative impact on Nicholson's work. Together, the couple travelled around Europe, encountering many of the most avant-garde artists of the day: Joan Miró, Constantin Brâncuși, Georges Braque, Piet Mondrian and Picasso. Several elements in 1932–34 (head) reveal Nicholson's stylistic debt to Picasso at this time: the head in profile, the repeated use of lines, the spiral-pupiled eye.

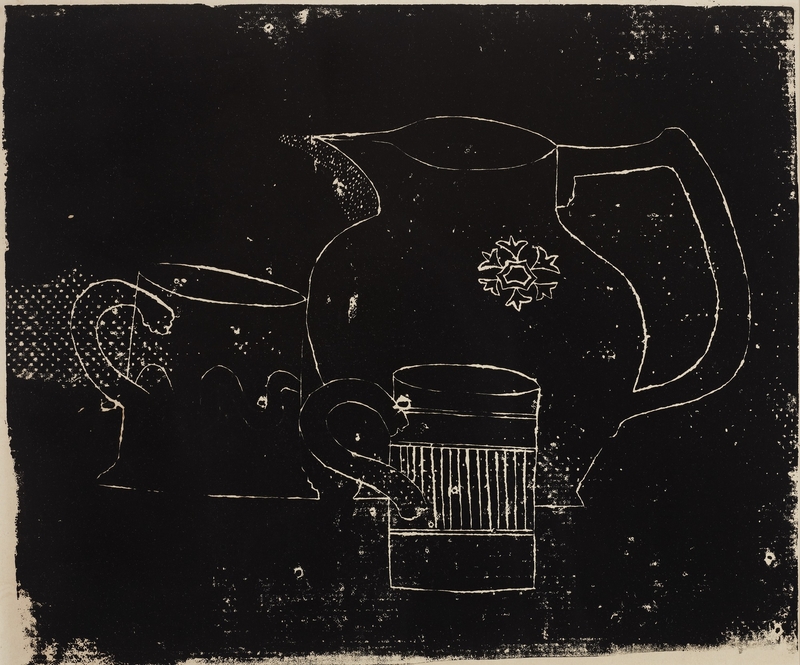

Nicholson was introduced to Cubism on a visit to Paris in 1921, and in the following years, his still lifes took on aspects of the style, with the shapes of his jugs, mugs and goblets becoming flatter and more abstracted.

1927–29 (jug and two mugs)

1927–1929

Ben Nicholson (1894–1982)

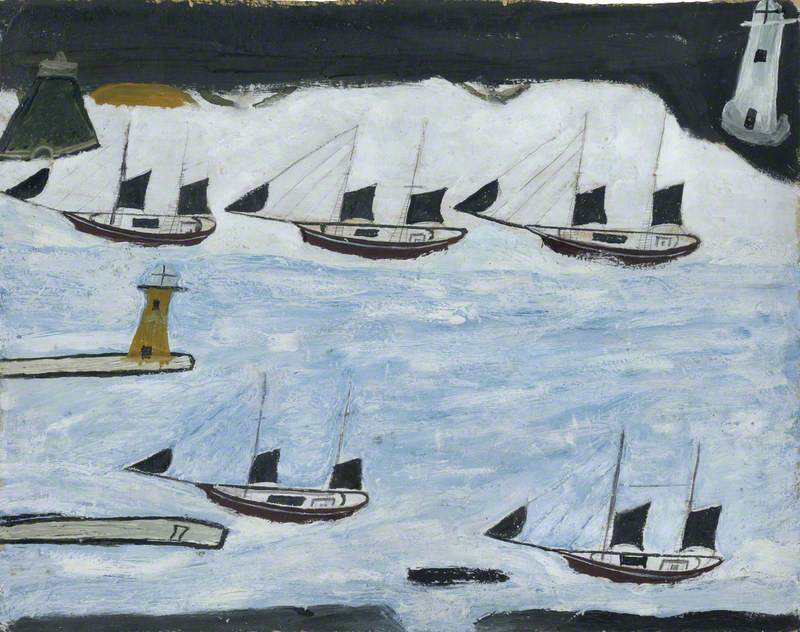

Another influence from this time was the Cornish artist Alfred Wallis, whose roughly textured surfaces Nicholson emulated after first encountering the artist in 1928.

In 1933 Nicholson and Hepworth joined 'Abstraction-Création' – a loose association of artists formed in Paris to challenge the influence of the Surrealist movement led by André Breton. Nicholson's membership in this group is perhaps surprising because head, made the same year, is quite Surrealist in style. The composition of the work, with what looks like a string dropped onto a piece of paper, fits with the Surrealist technique of spontaneous image-making.

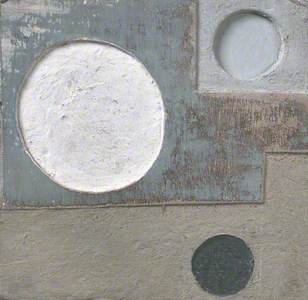

A year later, in 1934, Nicholson made his first geometric 'white relief' in painted wood, using only circles and straight lines. These works were among the most original examples of abstract art made by a British artist at that time and placed him as a foremost proponent of British Constructivism, along with Hepworth.

Like the looping patterns within the image, head has multiple, intertwined meanings. It marks a critical moment in Nicholson's career and crystallises the artistic exchange and collaboration in Nicholson and Hepworth's relationship. It is also a simple and beautiful expression of Nicholson's love for Hepworth – one that he performed repeatedly, like an act of devotion.

Naomi Polonsky, Assistant Curator, Kettle's Yard