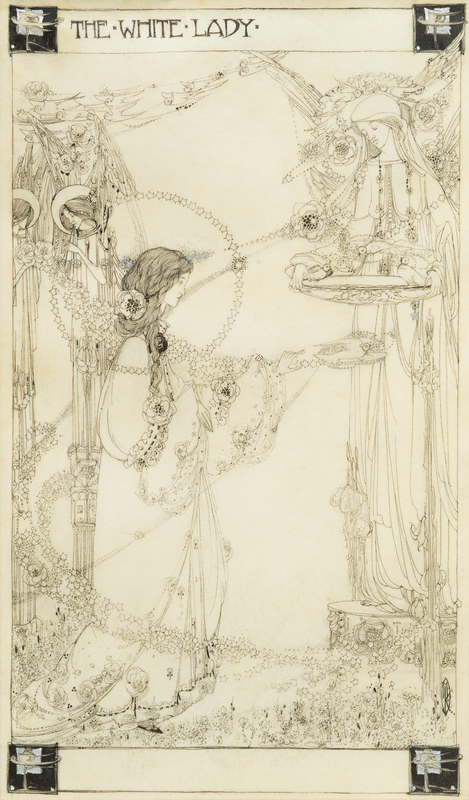

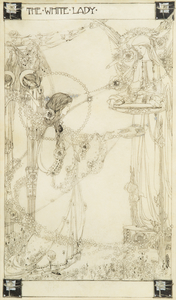

Jessie Marion King held a lifelong fascination that fuelled much of her work. The illustrator and painter, who was born at New Kilpatrick in Dunbartonshire in 1875 and became known as one of the Glasgow Girls, was famous for her enchanting images of fairies.

Jessie's lifetime interest in creating these ethereal images stemmed from a curious incident she had experienced as a child. The artist, who studied at Glasgow University and Glasgow School of Art, had fallen asleep on a hillside in Argyll when she was a teenager, and claimed to have felt the touch of fairies as she slept. King became an avid believer in Scotland's 'wee people' after this spiritual event.

This can be seen in many of the drawings, murals and children's book illustrations that she created during her celebrated career.

Fairies – or faeries – are an important part of Scottish folklore. They are said to be able to change their shape and size, although many appear in tiny human form.

While King's paintings depict fairies as the joyful creatures we recognise today, legend has it that these beings can be rather devious and enjoy playing tricks on humans. The female, although beautiful, is thought to be particularly malevolent.

Scotland's fascination with 'wee folk' dates as far back as the thirteenth century. The famous folk ballad, Thomas the Rhymer, which is thought to have been created by the Scots poet and prophet Thomas of Erceldoune, details an encounter with the Queen of Elfland.

In the song, Thomas speaks of meeting a fairy queen who was dressed in green and riding a horse with silver bells in its mane. The ballad is a cautionary tale that warns mortals against eating or drinking anything a fairy offers them, as it may prevent them from ever returning home.

It's little wonder that vivid depictions such as this one inspired so many of Scotland's artists, who took these folklore tales and made them central to their work.

One of the darker aspects of fairy folklore is the concept of changelings. According to legend, when a fairy steals a child, it leaves a changeling in its place. The changeling may look identical to the stolen baby, but will display characteristics that will alert its parents to the fact that their child has been replaced – including a change in behaviour, such as crying a lot or failing to grow or develop as it should.

Of course, these days we would recognise this as something else – such as ill health – but back when superstition was rife, parents would believe that their child had been replaced.

Oskold and the Elle Maids

1873–1874

Joseph Noel Paton (1821–1901)

In a bid to get their baby back, anguished parents would leave a 'changeling' out on a fairy hill at midnight in the hope that the 'fairy folk' would see one of their own in peril and take it back into the fold, returning the 'stolen baby'.

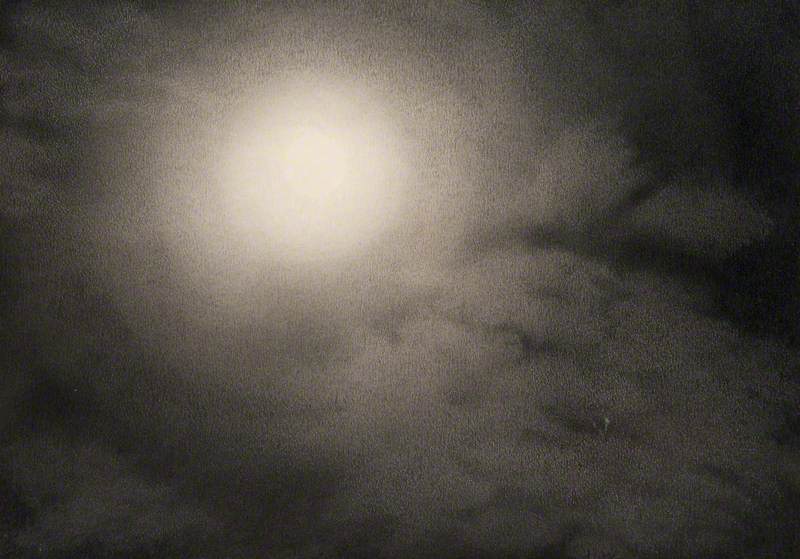

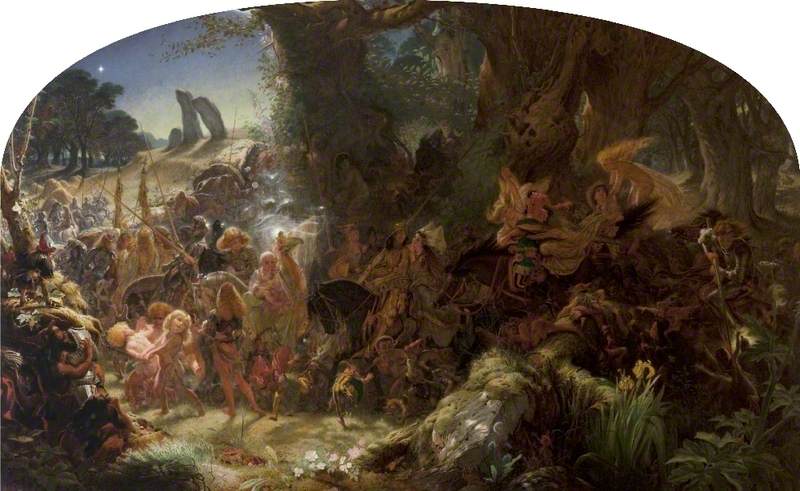

Such a nightmarish scene is depicted in Joseph Noel Paton's powerful and disturbing painting The Fairy Raid: Carrying Off a Changeling, Midsummer Eve. This was just one of many fairy paintings by Paton.

The Fairy Raid: Carrying Off a Changeling, Midsummer Eve

1867

Joseph Noel Paton (1821–1901)

Set in a moonlit, magical forest, this surreal oil painting shows a fairy queen carrying a young babe on horseback through a sea of bewitching creatures such as elves, pixies and brownies.

To the left of the image, a group of standing stones are illuminated on top of a hill. In folklore, these stones were often seen as the gateway to fairyland.

This image may look enchanting at first glance, but on closer examination, sinister details start to emerge – knights in armour ready for battle, creatures on horseback slaying other beings, and human children, chained by the leg.

These paintings and the stories that inspired them became increasingly popular during the Victorian era. Faced with poor living conditions and high mortality rates, the Victorians sought comfort in the possibility of life beyond their mortal existence.

It's no surprise that there was also a resurgence in the popularity of Shakespeare's work during this period, reflected in the artwork of the time.

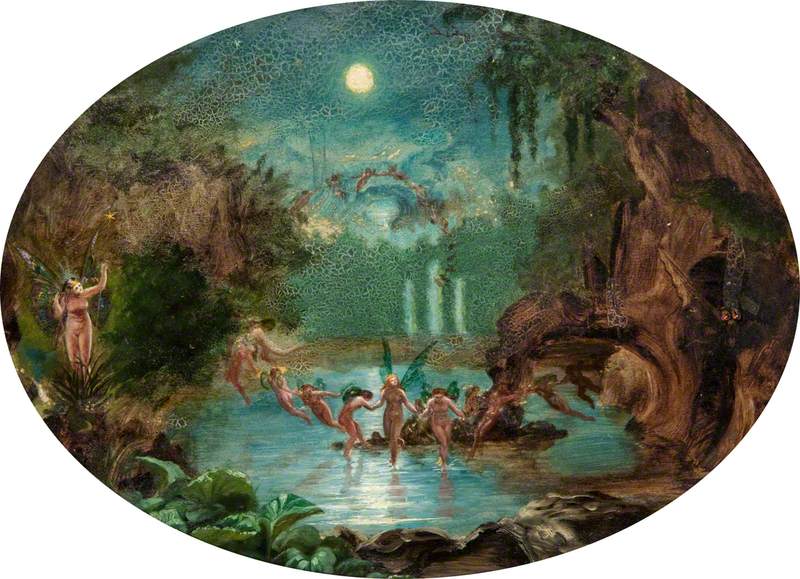

A Midsummer Night's Dream

(from the play by William Shakespeare) c.1900

Robert Fowler (1853–1926)

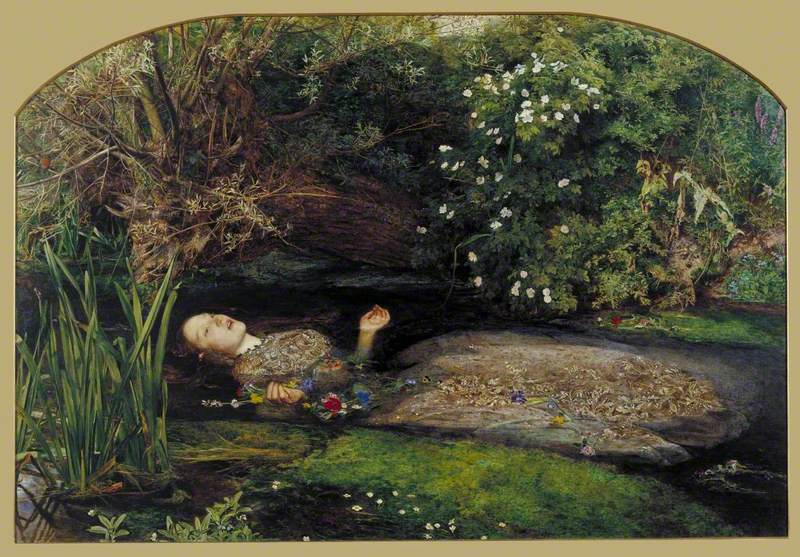

Paton recreated scenes from many of Shakespeare's plays. In 1849, he painted The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania, a work that illustrates a significant scene from A Midsummer Night's Dream, when the Queen and King of the Fairies fall out over the fate of a changeling, a disagreement that rocks the rest of the fairy community.

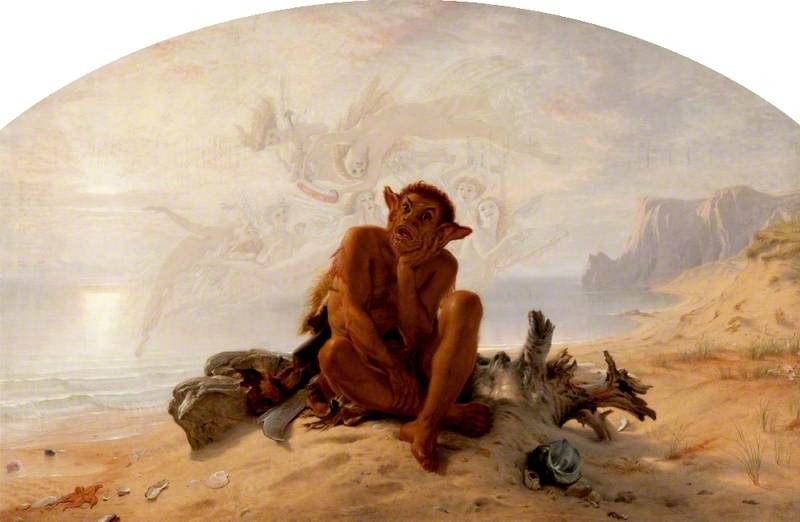

Another of Paton's works depicts Caliban, the son of a witch hag in Shakespeare's The Tempest. The painting shows the creature sitting cross-legged on a remote stretch of beach, while the island's haunting sprites float above the sea behind him.

Caliban

(from 'The Tempest' by William Shakespeare) 1868

Joseph Noel Paton (1821–1901)

The writer Arthur Conan Doyle was an avid believer in both spiritualism and fairies. When two young cousins, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, claimed to have photographic evidence of fairies dancing in a garden in West Yorkshire, Doyle employed experts to investigate the Cottingley Fairy photographs before printing them in The Strand Magazine. In 1922 he wrote the book The Coming of the Fairies about the incident and attempted to recreate the event in his own garden.

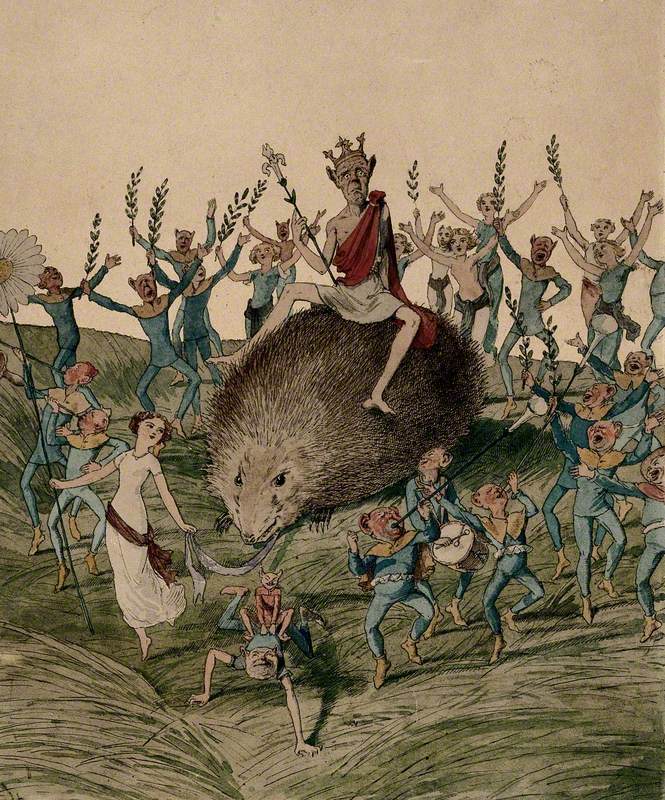

Doyle wasn't the first person in his family to have an interest in the supernatural. His father, Charles Altamont Doyle, who was an illustrator, drew on his interest in folklore and legend to create much of his work.

Doyle, who spent some of the last years of his life at what was then called the Montrose Royal Lunatic Asylum, painted the watercolour A Crowned Fairy King. The surreal, dreamlike image shows the fairy community celebrating their new king, through dance and song. An inscription reads: 'The seat of fairies is not always enviable.'

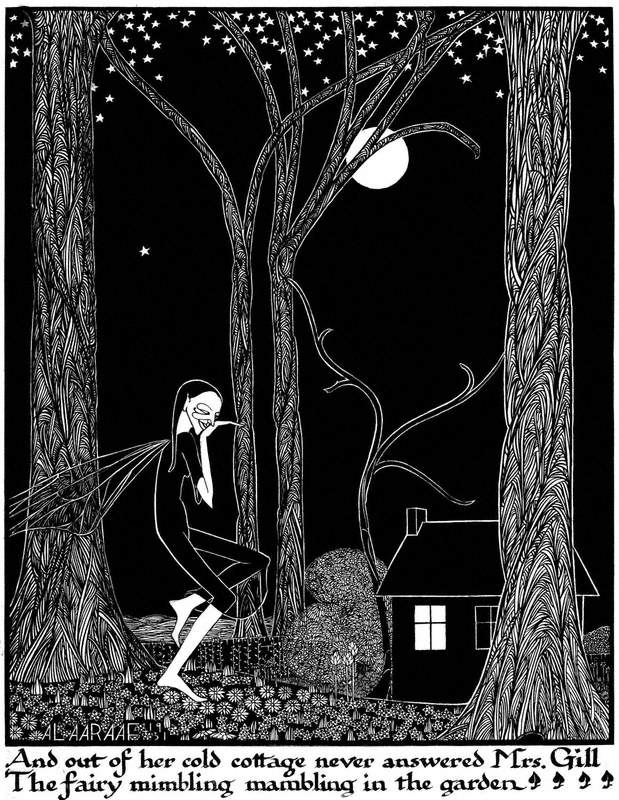

While Doyle's troubled mind produced joyful, childlike imagery, Edward Atkinson Hornel's depictions of these mythical creatures have a more sinister feel.

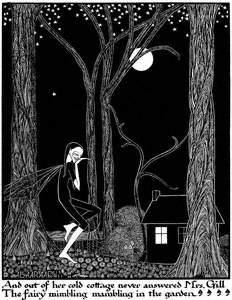

Hornel's pitch-black response to William Nicholson's The Brownie of Blednoch – a 32-verse poem about a bearded hobgoblin who scares Blednoch's villagers – is nightmarishly macabre. The haunting painting is very different from Hornel's usual vibrant style.

While our belief in fairies may have waned over the years, our affinity for them has not. In Scotland, illustrated tales about mischievous wee folk still delight younger readers and parents alike – but the devious side of these enchanting creatures, illustrated so well by Joseph Noel Paton and his contemporaries, has almost been forgotten.

Dawn Geddes, freelance arts writer

This content was supported by Creative Scotland