I settled on the north Wales coast in 2021, leaving the view of the Humber Estuary for the Irish Sea when pandemic restrictions were beginning to hesitantly lift in Wales. Working with communities and in the coastal and rural landscape as a curator has a profound impact on my thinking. My time here has shaped an interest in learning how cultures form through our bodies, and the relationship we have with the places we live.

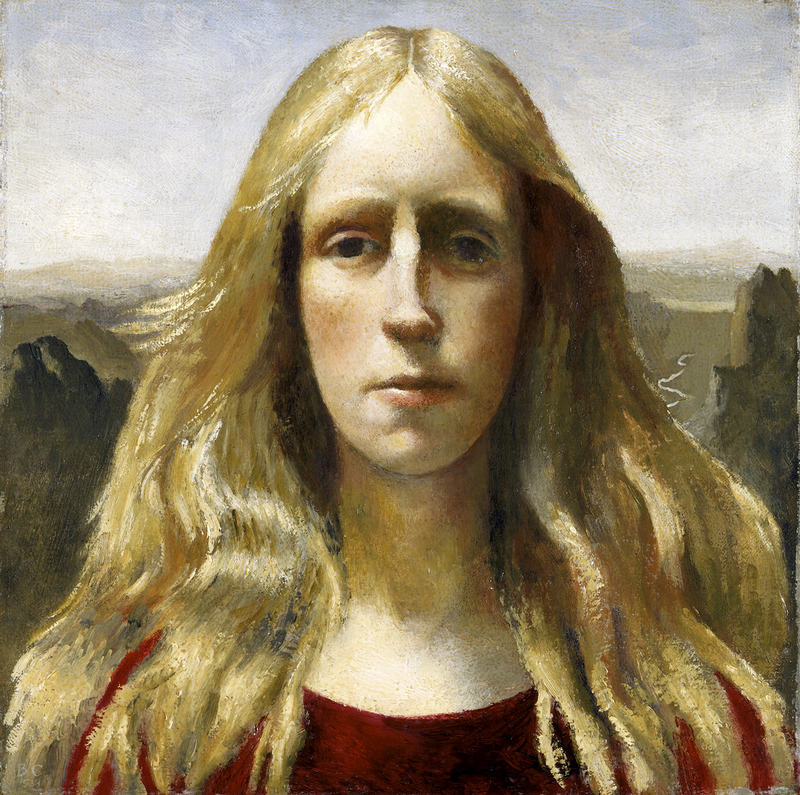

North Wales has traditionally been represented through paintings of rustic pastoral landscapes, dignified nineteenth- and twentieth-century civic portraits, and scenes of statuesque farmers working and not breaking a sweat.

A View Looking North along Conway Valley from Caerhun

Josiah Clinton Jones (1848–1936)

In contrast, communities in north Wales also face the harsh reality of concurrent crisis and funding cuts, which have contributed to public transport being unreliable and expensive, strains on social services and cultural and community spaces at risk of closure. Coupled with the vast 6,172 squared kilometres of coastline, hinterland and mountains, these pressures disproportionately affect those who are in poverty or isolated.

I approached this text seeking artists whose work counterbalances romanticised depictions of north Wales to tell a more nuanced story. Through my research, I discovered three artists at STORIEL – Susan Adams, Michael Cullimore and Dan Llywelyn Hall – who draw upon the erchyll, a Welsh term which means terrible or dreadful, which I learned through conversations with STORIEL Curator, Helen Gwerfyl.

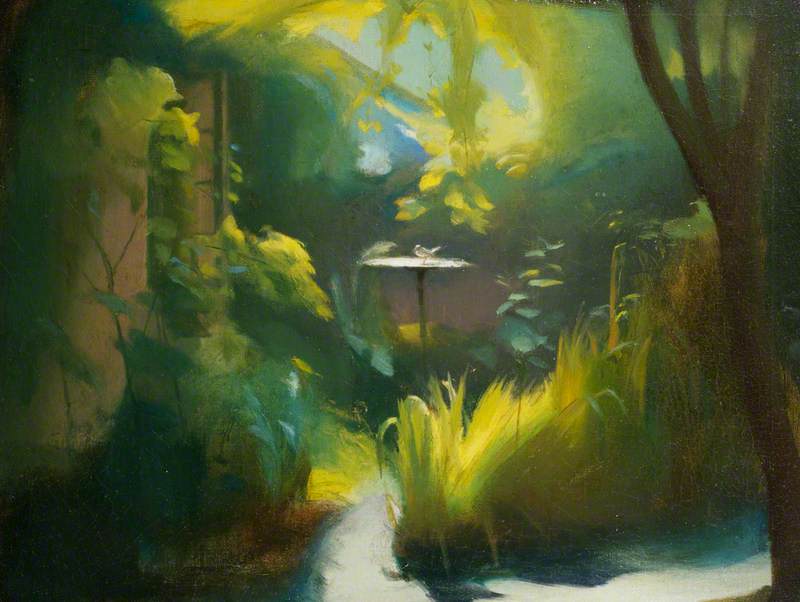

Susan Adams: thin places at the edge of the world

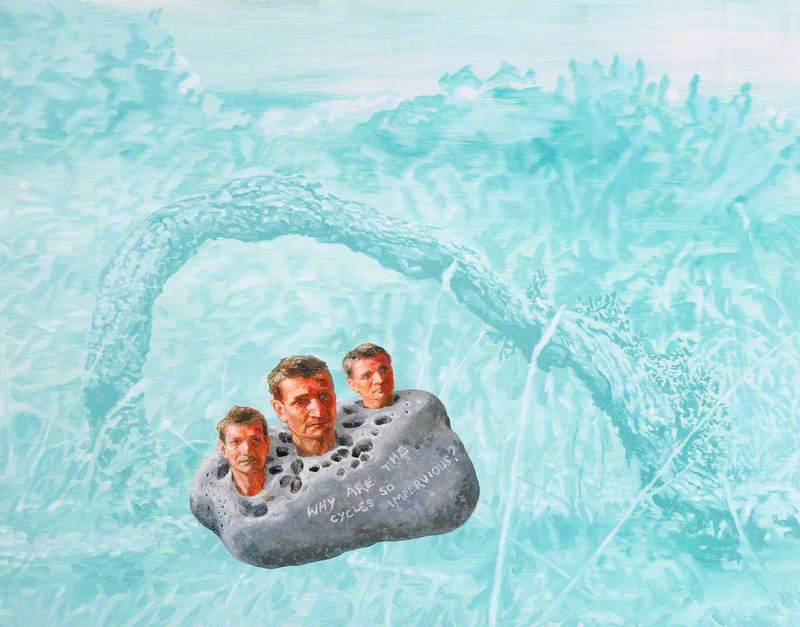

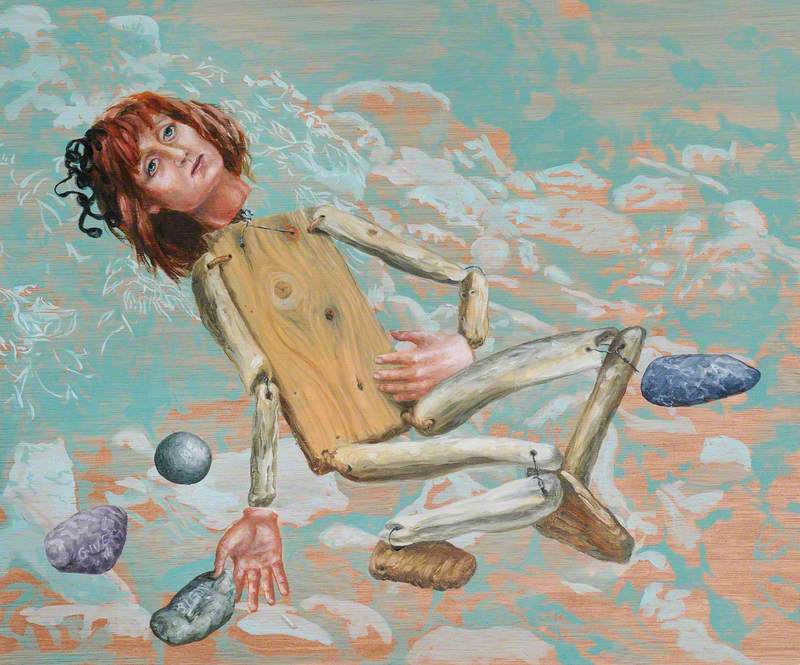

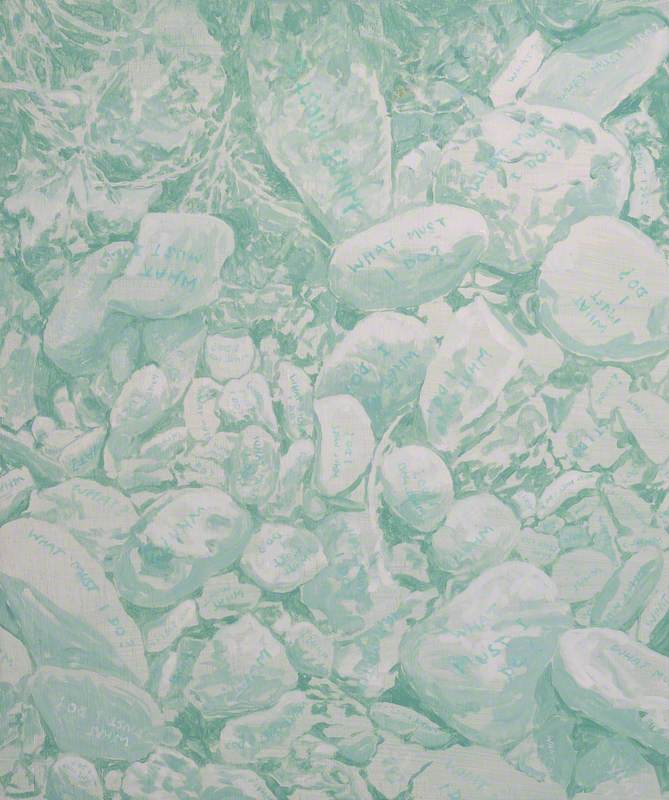

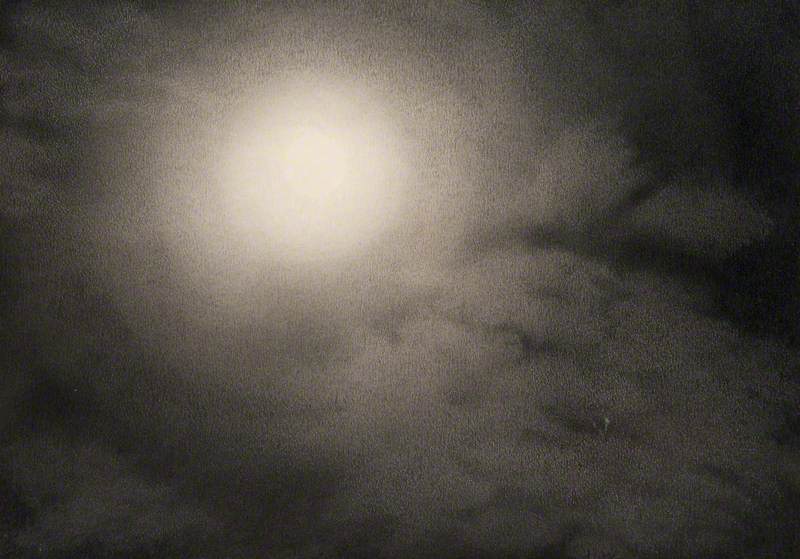

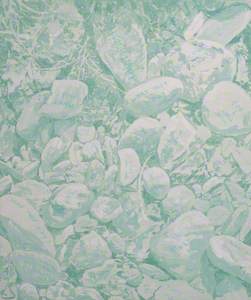

Susan Adams' Waiting for Something disrupts the peace with decapitated heads, a haunting marionette and stones etched with existential messages by an imaginary Saint Isiona.

The 30 paintings, made over 30 days, emerged from the artist's residency on Ynys Enlli in 2002 – the Island of Twenty Thousand Saints – which lies off the coastal tip of the Llŷn Peninsula. This important Christian site lures those seeking tranquillity, spiritual awakening, adventure and knowledge.

In an accompanying film, A Deep Breath, a young woman describes the island as a thin place, bordering heaven and earth, as Adams asks residents about the relationship between place and spirituality. 'I'm looking for nothing,' says an archaeologist 'I've found the skeletons of hundreds of people here' as he chips away at the ground and bones. Ynys Enlli is a burial site, hosting both the living and the dead.

The creation of Waiting for Something coincided with the re-energised climate change movements of the early 2000s, exposing how community, culture and history tethered to the geographical edges are at the mercy of ecological systems. A conversation I had with artist Catrin Menai, who lived on the island, revealed how turbulent weather conditions and sea currents often make travel to the mainland unpredictable, and food and water scarcity is a reality. How would an artist fare today in making works as the weather becomes more unpredictable and dangerous?

Michael Cullimore: digested and regurgitated bodies

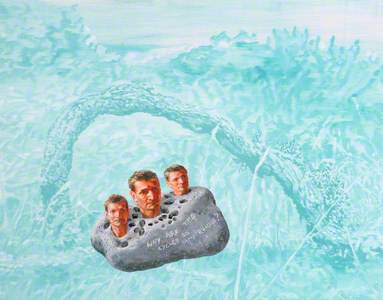

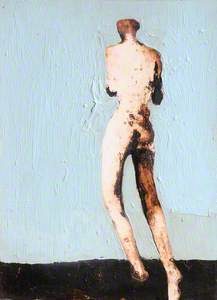

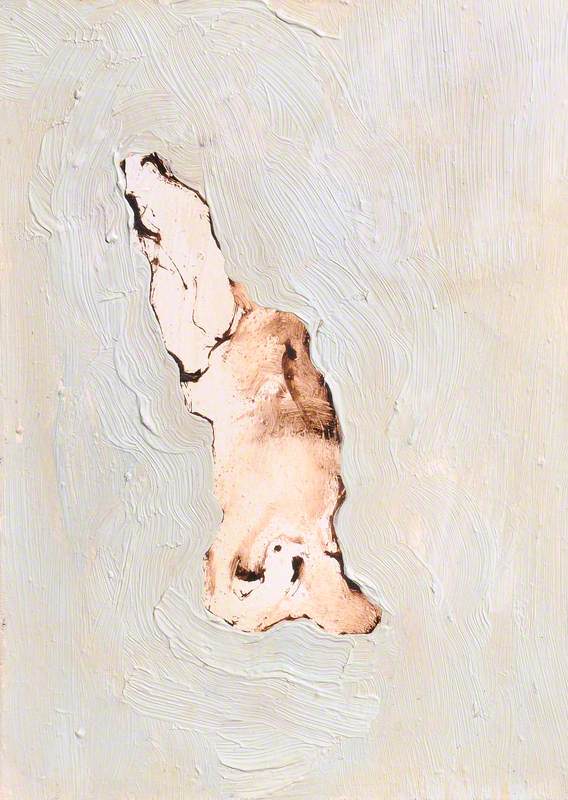

Michael Cullimore's Jonah – 16 Studies presents agonisingly twisted forms, painted on 16 small panels in oil, in a four-by-four grid frame. The studies give us a chronology of the biblical story of Jonah being caught in a storm, swallowed, digested and regurgitated alive by a whale.

Jonah – 16 Studies

(panel 3 of 16) 1971

Michael Cullimore (1936–2021)

The focus of Cullimore's art is moments of change, transformation, birth, decay and death. Painted at the age of 35, during his tenure as an educator and curator at Bangor University's museum and art gallery, this series feels part of a frightened legacy of works depicting trauma and humans being consumed, like Goya's Saturn Devouring His Son and contemporary pop culture interpretations such as Attack on Titan (Shingeki no Kyojin in Japanese).

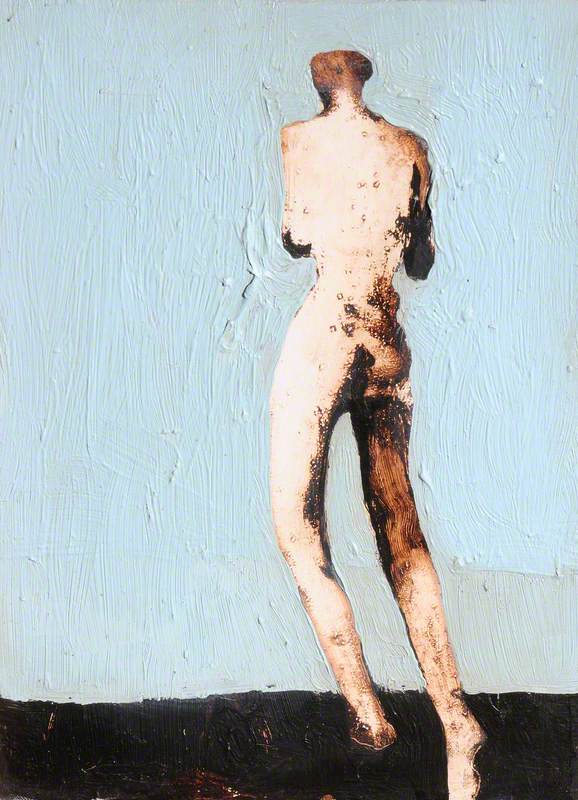

Jonah – 16 Studies

(panel 7 of 16) 1971

Michael Cullimore (1936–2021)

After his marriage to a wife from north Wales, they settled here and renovated a derelict cottage, starting a family of four children alongside pigs, chickens and a small Jersey cow. However, Cullimore's obituary reveals just over a decade after making these works he was 'forced to retire due to ill-health' aged 47, and left Wales to return to Wilshire. His later life was coloured by the pain of osteoporosis, and he was registered blind. Regardless, he continued to paint and work in the studio until he passed away in 2021.

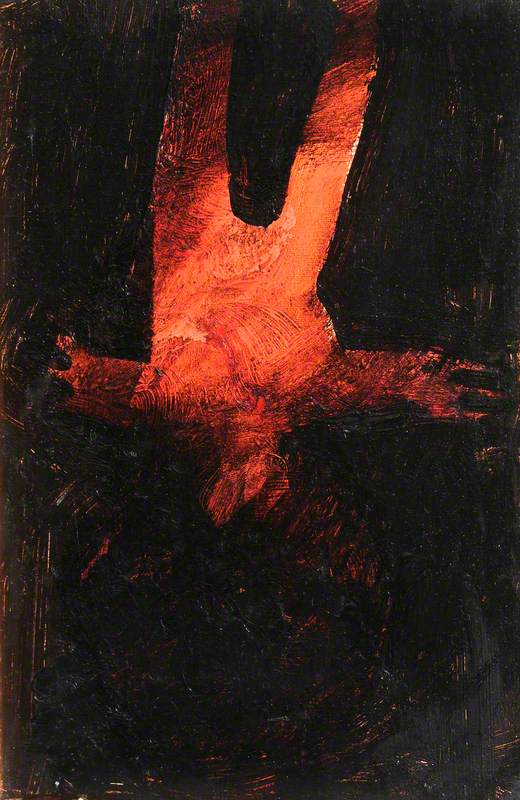

Jonah – 16 Studies

(panel 11 of 16) 1971

Michael Cullimore (1936–2021)

Jonah's chewed form floating in pale waters feels prophetic to Cullimore's later illness – perhaps they were made as the symptoms of his conditions started to emerge. If we read this story through the lens of the Social Model of Disability, which states that the barriers in society disable us, not our impairments, this suggests his employer or the rural landscape could not accommodate Cullimore as his health deteriorated.

The swallowing of Jonah warns of our vulnerability. Bodies further disabled by rural isolation and regional inequality are especially vulnerable when access to medical and social care is beyond our reach.

Dan Llywelyn Hall: a scar etched into the landscape

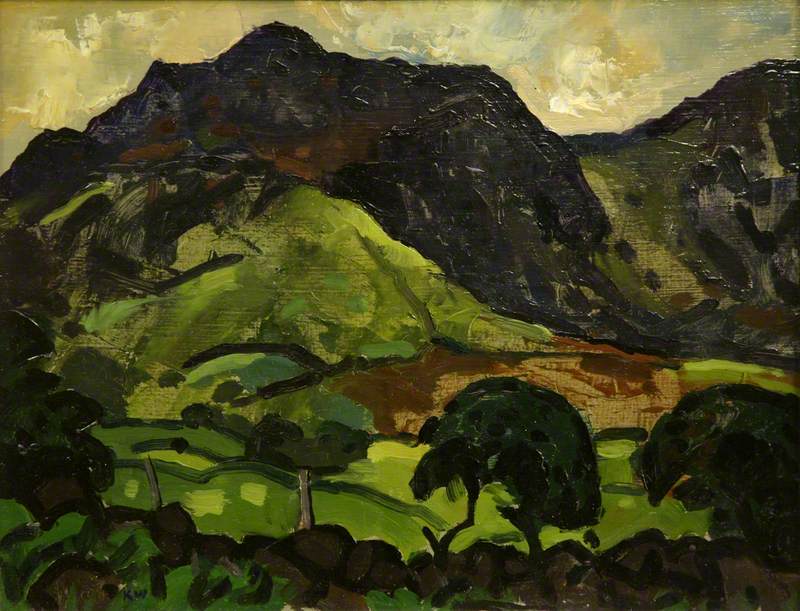

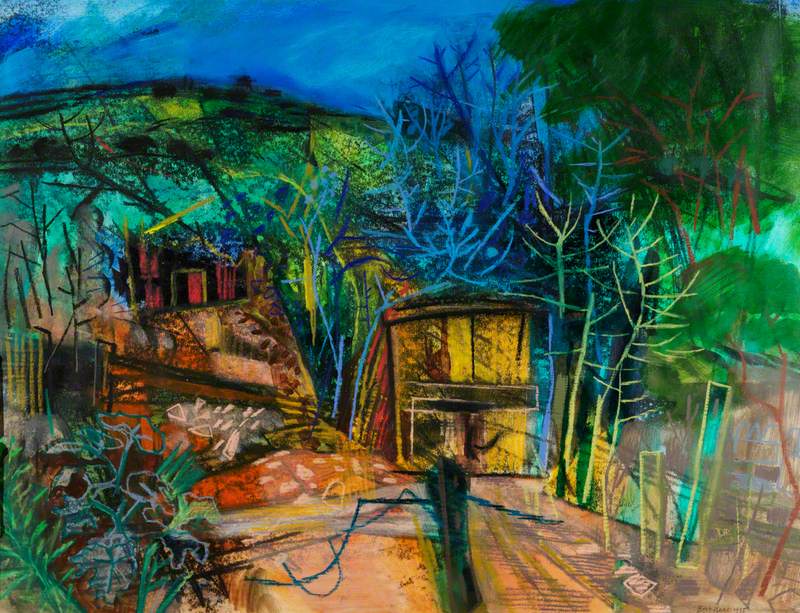

In Dan Llywelyn Hall's gestural painting of the Cambrian landscape, the subtle roundel of a Royal Air Force Canberra bomber peeks out among the mangled and scattered remnants, after crashing into the slopes of Carnedd Llewelyn in 1957.

Crew members William Albert Bell (31) and Charles Frederick Shelley (27) lost their lives in the crash, which was caused by engine failure due to ice. The area was once dubbed 'The Graveyard' because so many aircraft had crashed there, where clouds often shroud the mountaintops.

Hall's painting shows a literal human impact on the land: an object of war scored into the landscape in paint. With bases located on Anglesey and Barmouth, Eryri often sees fighter planes fly over its peaks for routine training, perhaps a reminder of Wales' complicated history under British feudalism and imperialism.

The repercussions of centuries of ancestral subjgation, attempted erasure of Welsh culture, the exploitation of workers and extraction of resources is still felt in many Welsh communities. These oppressive strategies and violent histories exist within a long history of the British state's domination of working-class communities across the UK, and colonialism abroad – to which Wales was also an active participant.

I'm easily seduced into critique of these powerful institutions, but we shouldn't lose empathy for the young pilots who lost their lives. The ruin is also their testimony.

Bleak forecasts to find new paths

The morose subjects and contexts of Adams, Cullimore and Hall's work explore how the landscape and the cultures held within it have value – including the parts that make us feel uncomfortable.

Art is a powerful tool to tell meaningful stories, including those of scarcity, inaccessibility and tragedy. Isolated communities like those dispersed across remote areas in north Wales, without sufficient infrastructures, are most affected by ecological, economic and social crises and their byproducts (like war); and protecting those on the periphery is what perhaps might bring wider social salvation. Perhaps artists who bring the erchyll into their work can teach us, and instil in us a sense of urgency and advocate for change.

David Cleary, curator and facilitator

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding