Airbrushing and Photoshopping have become ubiquitous in the images we see around us. But these tools, once the preserve of fashion magazines, have now been superseded by the likes of Facetune, social media filters, and even 'deepfakes'. With generative AI like DALL-E, it's getting harder to tell a real human body from an artificial-intelligence creation.

But although those who are keen to change the appearance of the human body with technology today may think they are doing something new, in reality, they are not the first to treat the human form as malleable. There is a long history in art of seeing the human body as a canvas or the subject of transformation.

Drawing the human figure is often one of an artist's earliest exercises. Though it requires just a pencil and paper (and not a powerful computer using AI), its economy of materials doesn't mean that it's simple or simplistic. For many artists, drawings are an efficient way to execute their most groundbreaking visions.

In the twentieth century, a variety of British artists used drawings to experiment and subvert viewers' expectations about the body. The prevailing art world trends at the time focused on large-scale paintings and sculpture, and often turned away from figurative art, so these drawings offer a different narrative. They re-envision the figure and redefine corporeality, prompting the viewer to consider what constitutes authentic humanity.

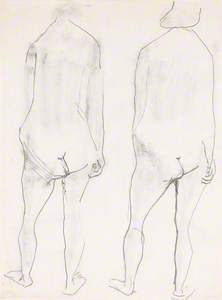

Kenneth Armitage (1916–2002)

Best known as a sculptor, Leeds-born artist Kenneth Armitage received the Gregory Fellowship to attend the Leeds College of Art from 1953 to 1955. There, he studied in the wake of Henry Moore, whose supple, dimensional sculptures he would react against.

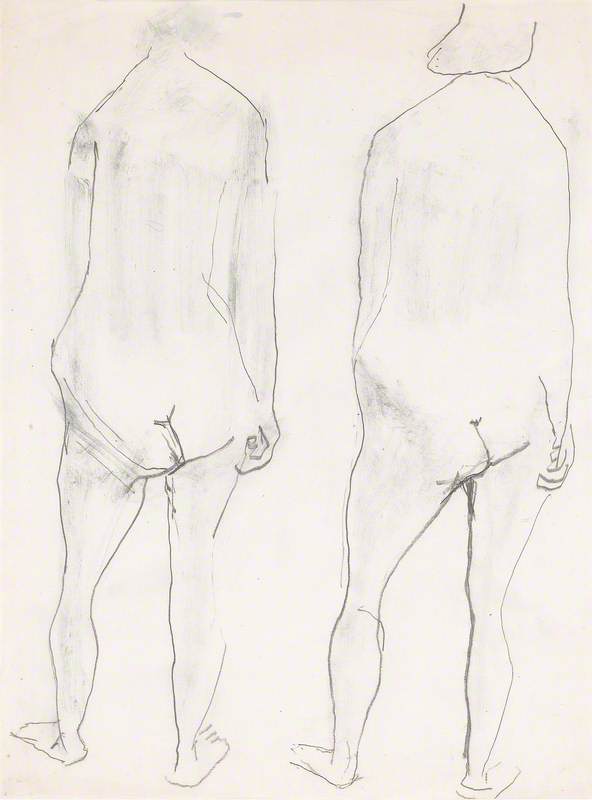

Armitage's great subject was the human form, his material bronze and occasionally other metals. Yet while his sculptures such as Diarchy (1957) or Children Playing (1953) depict interlinked bodies, in his 1952 drawing Two Standing Figures, Armitage experiments with isolation. Using pencil and wash, he depicts in posterior two similarly sized figures. A limb blurs into a notched waist; a neck leads to nothingness; a head goes tubular. In its economy of line and shading, Armitage's drawing investigates the weightlessness that characterises his three-dimensional works.

Two years after being honoured as the best British sculptor under the age of 45 at the 29th Venice Biennale in 1958, Armitage completed the haunting, mischievous Life Drawing. Is this female figure suspended in space? Reclining on an invisible branch? And why does one elbow sprout two forearms? As Armitage said, 'I find most satisfying work which derives from careful study and preparation but which is fashioned in an attitude of pleasure and playfulness.'

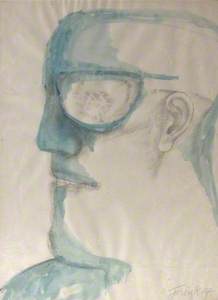

Elisabeth Frink (1930–1993)

Violence and monstrosity marked the work of Dame Elisabeth Frink. The impact of the Second World War was heavy: her father was a soldier at Dunkirk, and she spent years of her childhood living in Suffolk near an airfield. She survived a German fighter plane's machine gun assault by secreting herself away in shrubs.

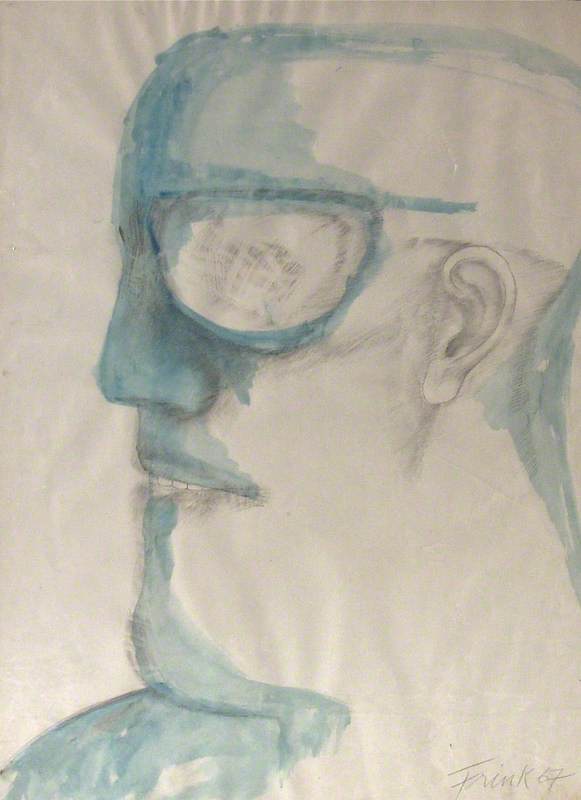

Frink sold her sculpture Bird to the Tate Gallery in 1953 while she was still a student at Chelsea School of Art. In the late 1960s, Frink began her acclaimed 'Goggle Head' series: bronze busts of men's heads with goggles or glasses hiding their eyes. These sculptures, Frink said, 'became a symbol of evil for me.' In fact, Frink's work was so synonymous with atrocity that she created the sculptures and served as a consultant for the 1963 science-fiction horror film The Damned.

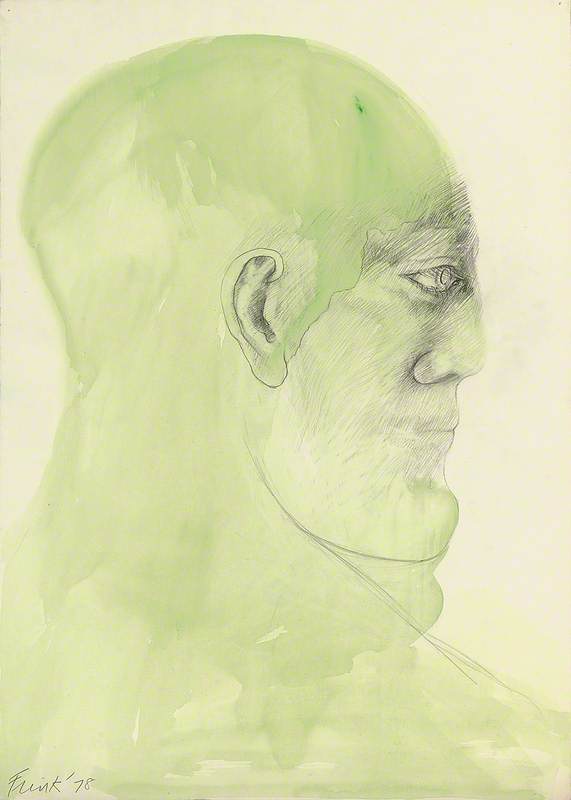

Green Head, in title and subject, evokes the 'Goggle Heads'. The skull is similarly elongated, the chin thrust. And yet, here a nauseating green watercolour wash colours the flesh. Crudely drawn eyes stare forward, perhaps aware of the facial features seeming to dissolve.

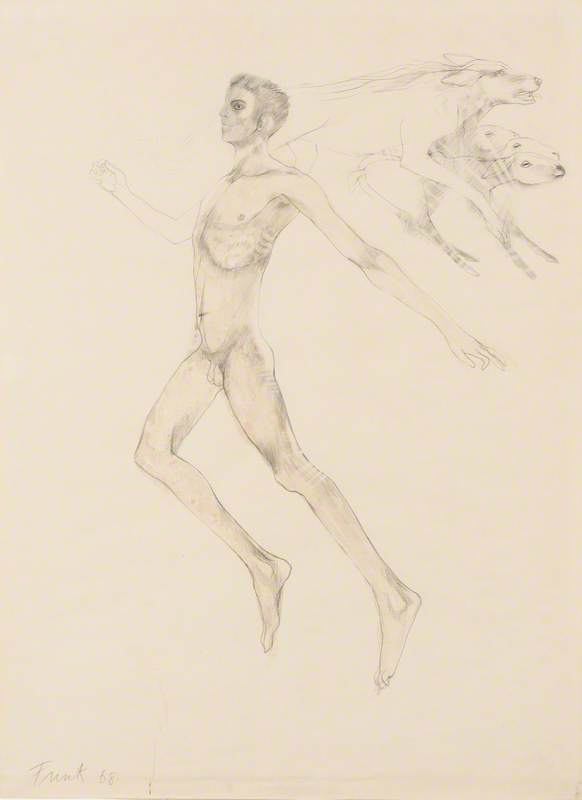

Known for depicting birds and horses, Frink expands her repertoire to include the canine with The Boy Who Cried Wolf. (In her personal life, she was a dog lover.) Here, she illustrates the classic fable inside-out, making the metaphoric literal, with a depiction of transmogrification. Rendered in pencil and watercolour, the male body seems both to be pulled forward and yanked back. What's holding the figure taut is none other than a wolf, streaming out of the man's head. But this is no simple canine. Below it, Frink draws three sheep, suggesting that the wolf, indeed, wears sheep's clothing.

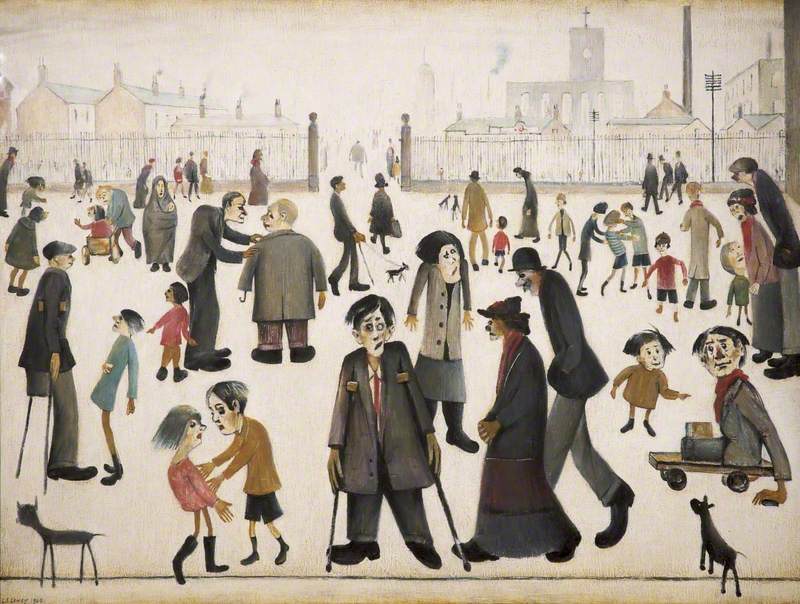

Laurence Stephen Lowry (1887–1976)

'You don't need brains to be a painter, just feelings,' Laurence Stephen Lowry said. He famously quipped that he was 'a Sunday painter who paints every day of the week' – he was a preternatural self-minimiser and he rejected a knighthood in 1968. Perhaps declining honours gave him more hours to work: he produced 1,000 paintings and 8,000 drawings in his 88 years. He was known for his 'matchstick men' and industrial landscapes. T. J. Clark, who curated the 2013 Lowry show at the Tate, called him 'a good painter, and a bad painter.'

Good and bad coexist in Lowry's 1973 drawing, Girl with Bows. The doe-eyed figure populates the other 'marionette' sketches that surfaced decades after the artist's death. Here, bow becomes fetish, engorging the girl's head and torso. Knees together, arms held stiff, mouth an O, she resembles a doll or puppet.

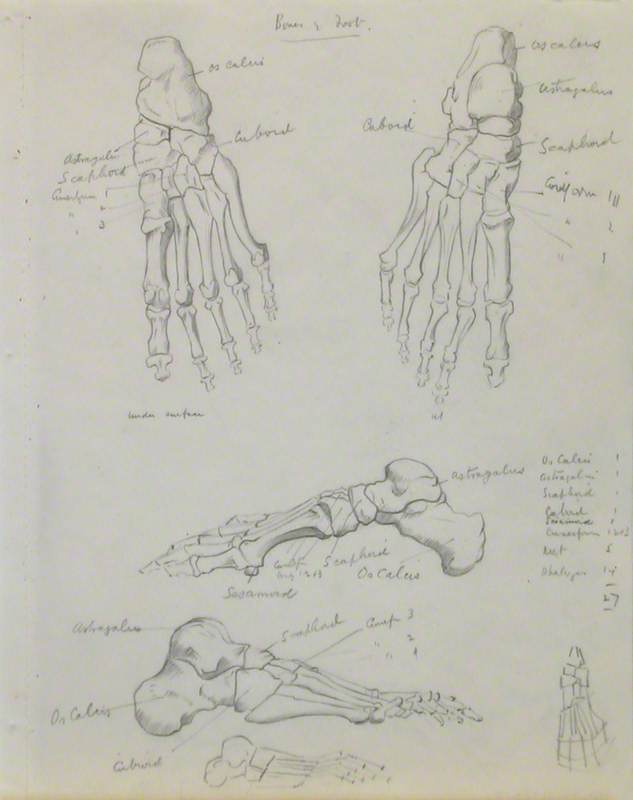

Skeletal Structures of Foot

c.1919–1920

Laurence Stephen Lowry (1887–1976)

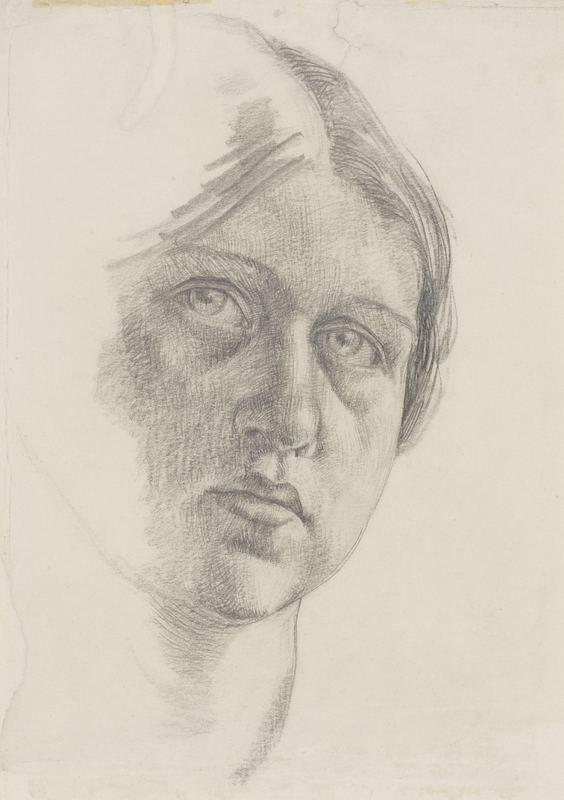

Dora Carrington (1893–1932)

Dora Carrington has long captured the public's imagination. The subject of the 1995 film Carrington (Emma Thompson played the painter) and the 2003 film Al sur de Granada, Carrington painted without public recognition for most of her life. Existing semi-adjacent to the Bloomsbury group (she worked for a time at Hogarth Press), Carrington's unrequited love for queer writer Lytton Strachey came to define her. The isolation she felt is apparent in her landscapes, such as in Spanish Landscape with Mountains, which renders mules and muleteers minuscule before rolling Andalusian hills.

This early untitled drawing, thought to be done when Carrington was 17, is a rare self-portrait. Depicting herself with her long hair pulled back, Carrington uses pencil to capture her own plaintive expression. Eyes gazing just upwards, mouth pursed, the face suggests wistfulness or, perhaps, hope. Yet one side of the portrait seems absent: thick lines of hair and cross-hatching of skin dissolve into shocking blankness.

In this later self-portrait, not only has her self-presentation changed (hair chopped short, striking outfit featuring ballooning trousers), but the way she draws her body has, too. The work has a flatness and modernist aesthetic that is absent in her earlier drawing. Rather than seeming to disappear into white paper, Carrington is strikingly dense, with a dark outline and tangible presence. Her whole body is represented on paper, rather than just her head, making a larger claim of space and refusing to shy away from her corporeality.

Patti Mayor (1872–1962)

Patti Mayor was a Suffragette and a painter. Her activism is apparent in her art, which depicts, again and again, the working-class girls and women of her Preston home. Portraits have long been reserved for royalty, aristocracy, and the upper class. By making common folk her subject, Mayor created a body of work that demonstrated her commitment to equality.

While Mayor frequently worked in oils, she used pastels for her drawing Audrey. Here, the subject's tight orange-red curls contrast with the Prussian blue of her dress and hairbow. Far from an ornate gown, the dress has a slender lace collar adorned with an ornament or nosegay. But Mayor captures more than sartorial choices. The young woman faces the viewer head on, cheeks ruddy, mouth upturned. Is she smirking or smiling? The arch of her eyebrows suggests the former. What secrets does she keep?

As Simone de Beauvoir wrote in The Second Sex: 'The body is the instrument of our hold on the world.' In their drawings of the human form, these artists challenge us to rethink that instrument and how it grasps this world.

JoAnna Novak, writer and poet

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation