The panel painting Lady in a Court Dress has always been a popular fixture at Ordsall Hall, formerly hung in the Great Hall and more recently in the Great Chamber. Now, after recently undergoing repair work, 'our lady' has given up more of her secrets. While the painting was away, the opportunity was taken to have her x-rayed, looked at through infrared light and appraised by a costume specialist.

'Portrait of a Lady in Court Dress', before restoration

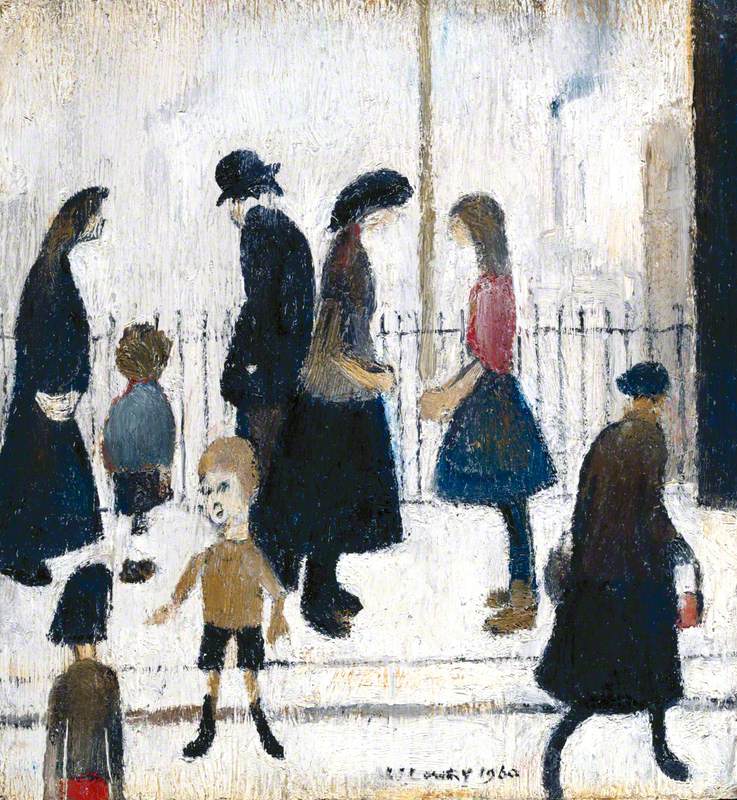

This work has been previously attributed to, or thought in the manner of Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (1561/1562–1635/1636), a Flemish painter who worked at the Tudor court. Gheeraerts was the son of an animal painter in Bruges. He came to England soon after 1580, but his earliest known works date from 1592: therefore this work would be very early in the artist's oeuvre. Later in his career, Gheeraerts was appointed painter to Elizabeth I and Queen Anne of Denmark. He is particularly remembered for his portraits and paintings of royal state occasions. He remained in England until his death.

Lady in Court Dress is believed to be by a British contemporary of Geeraerts and probably dates to about 1590. The treatment of the clothing and the sitter's posture are both derivative of Marcus Geerearts' 'Ditchly portrait' of Elizabeth I.

Queen Elizabeth I ('The Ditchley portrait')

c.1592

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (1561/1562–1635/1636)

The portrait at Ordsall Hall is painted on panel, which consists of four separate pieces of wood joined together. Unfortunately, one of these joins had failed, hence the need for restoration work. The repair was even more complicated as there was a natural curve in all panels giving the painting a convex appearance. In addition, there were many layers of varnish and the work had not been fully cleaned since the 1950s.

Rebecca Kench, conservator, working on the painting

Restoration work was confined to the failed join area where overpaint and old glue was removed. Once the new glue was applied it was left under tension and supported for 24 hours. Any gaps in the join were filled with a combination of coconut flour and micro-balloons. A jelutong baton was made and fixed to the reverse to mirror the other batons which were already present. The join was retouched, and several top layers of Dammar were applied to match as closely as possible to the adjoining varnish.

The x-ray revealed the most striking discovery. It showed that the artist first painted the woman with a long string of pearls around her neck.

X-ray image of 'Portrait of a Lady in Court Dress'

X-ray image of 'Portrait of a Lady in Court Dress'

For some unknown reason, the pearls never appeared in the finished portrait, but it does account for the strange position of her right hand which was meant to be touching or holding some of the pearls.

Detail of 'Portrait of a Lady in Court Dress'

The infrared image showed that the sitter's headdress goes all the way around her head – not just the top where it is visible.

Infrared image of 'Portrait of a Lady in Court Dress'

An appraisal of the costume confirmed the style has all the hallmarks of the period 1590–1600. It is likely a black silk velvet gown with trunk sleeves that are headed with gold ouches set with pearls. The stomacher front also has applied ouches set with pearls and precious stones in an alternating layout. Of note, there is early needle lace in the modesty piece at the top of the stomacher. The ruff and the cuffs are of very fine starched linen. The ring on her finger is connected to black silk cord that wraps around her left wrist.

The muff is unusual in that they are not seen that frequently in Elizabethan portraiture: women are usually depicted carrying fans or gloves, or occasionally a small prayer book. The muff appears decorated with applied metallic cord or braid and trimmed with either fox fur or sable.

Portraits of other ladies in Elizabeth I's service in the 1590s are in the court dress of white and silver – indeed Geeraerts did a painting of one of her maids, Lady Elizabeth Southwell, wearing those colours. So, the most remarkable discovery is that it is likely that our lady is not a court lady after all… unless she is a maid and it is her day off!

Salford Museum & Art Gallery bought the painting at the auction of Abney Hall, Cheadle, Cheshire in March 1958. Formerly owned by the Watts family, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited Abney Hall in 1857, at the time of the Manchester 'Art Treasures Exhibition'. There is speculation several of the paintings at Abney were 'touched up', including our 'Court Lady', to make them more presentable to the royal couple. It is also alleged that the painting was formerly at Heaton Hall in north Manchester.

Further conjecture lies in the mystery of the sitter. Margaret Radcliffe of Ordsall Hall (1575–1599) was a maid of honour to Elizabeth I. Rumour says it is Margaret Radcliffe in the painting. There is no evidence to support this, the museum service bought it back in 1958 on the slim chance it might be. The following year, Salford Corporation bought Ordsall Hall.

'Portrait of a Lady in Court Dress' is returned to Ordsal Hall

Interestingly, after Salford Museum & Art Gallery purchased the painting, it was sent to Liverpool to be conserved by J. Coburn Witherop. Some 64 years later, this most recent restoration work also took place in Liverpool.

Peter Ogilvie, Collections Manager at Salford Museum & Art Gallery

Restoration work on Portrait of a Lady in Court Dress was undertaken by Rebecca Kench ACR, freelance conservator. The costume was appraised by Pauline Rushton, Head of Decorative Arts & Sudley House, National Museums Liverpool

The restoration was made possible thanks to a generous donation from North West developer ForLiving. Salford-based ForLiving, the ethical landlord behind the riverside 'Dock 5' community a stone's throw from Ordsall Hall, has sponsored the conservation of the oil painting